|

Help About Related Share Your Story General Mall

Food Court Retail Entertainment Management Souvenirs Related Links

|

UrbanRetailPropertiesCo

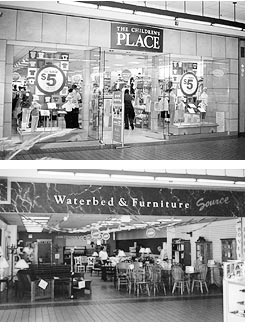

Savvy Specialists Help 'Sick' Malls Get BetterJanuary 26, 2004 By Dean Starkman From The Wall Street Journal Online POTTSTOWN, Pa. -- Rene F. Daniel walked the floor of Coventry Mall here recently, looking for ways to squeeze more sales out of this 1960s-era regional mall. He stopped in front of a problem: Arby's. The tired-looking fast-food outlet was generating weak sales relative to other stores lately, despite its prime location by a mall entrance. "That one's not going to make it," Mr. Daniel said, shaking his head. His plan: Force it out. Meet the mall doctor. A 30-year real-estate veteran, Mr. Daniel is one of a growing cadre of professionals who specialize in resuscitating dying shopping malls. His remedy for Coventry -- a multipronged effort including store shuffling, ejecting poor performers, attracting desirable tenants and general renovation -- is part of a wider struggle on the margins of malldom: The country has too many malls, and many just aren't going to make it. Analysts estimate that up to a third of the nation's 1,200 malls are obsolete or nearly so. After a decade of consolidation, the 10 largest mall real-estate investment trusts now control 47% of all malls -- nearly all of the 200 high-performing "A" quality properties and most of the B's. In addition, 10 or so shiny new malls are built a year. These top malls increasingly dominate shoppers' dollars.  Top photo: A store at the revamped Coventry Mall in Pottstown Pa. Bottom photo: a former Coventry tenant. That leaves a large list of downscale malls owned by families, trusts with diverse holdings and other smaller operators -- like Coventry's landlord, closely held Goodman Co. of West Palm Beach, Fla. -- many of which don't have the resources or the know-how to compete. Second-tier malls are especially hurt by faltering lower-price department stores, such as J.C. Penney Co. and the now-defunct Bradlees, and competition from Wal-Mart Stores Inc. and other nonmall discounters. "About 20% are 'D' malls, which need to be de-malled," quips Lee Schalop, a Banc of America Securities analyst. Malls are expensive to demolish and nearly impossible to convert to another use. Dead malls are often crime scenes and a drain on local tax rolls. The landscape is already pocked with dead or dying eyesores, such as Dixie Square in Harvey, Ill.; River Roads in Jennings, Mo.; and Beloit Plaza, in Beloit, Wis. And dozens more are on the margins, creating a growing market for turnaround specialists, which include national powers Jones Lang Lasalle and Urban Retail Properties Co., both based in Chicago. Urban, for instance, was hired in late 2002 to assess the viability of the Mall of Memphis, in Memphis, Tenn., which some local wags called the "mall of murder" after the mid-1990s robbery and murder of a store manager. The owner, a Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. unit that took control of the property in 2002 through a foreclosure, decided to close the property as of the end of last month. A Manhattan native and economics graduate of Hunter College, the 59-year-old Mr. Daniel has leased space on behalf of mall landlords since the 1970s. In the past decade, however, as publicly traded mall giants, like General Growth Properties Inc. and Westfield America Inc., bought or built the most productive malls in the best locations, Mr. Daniel began to advise small landlords needing help with faded property. Last fall, he formed a joint venture with a New Jersey-based brokerage, Metro Daniel LLC, based in Baltimore and Mount Laurel, N.J., to focus on mall rehab full time. When Mr. Daniel took over management of Coventry five years ago, the 1960s-era mall was undersize, tired-looking and, at 36% vacant, bleeding tenants. Its Bradlees anchor had gone dark, while its Foot Locker Inc. and Gap Inc. stores were cramped and dingy. It also had too many locals, like Westies Shoes, drawing too little traffic. And only 22 miles away was the sprawling King of Prussia Mall, the nation's biggest shopping complex. (The famed Mall of America, in Bloomington, Minn., has more total space but less shop space.) To save it, Mr. Daniel needed to cut the number of trips Pottstown residents took to King of Prussia to two or three a year, from five or six, and get shoppers to linger longer. Step one: Fix the food. Coventry had a six-stall food court with mostly local operators, "Hot Dogs & More," "Egg Roll Hut" -- but no burgers. McDonald's Corp. agreed to open a small 1,000-square-foot operation in 1999 and was followed by a Subway Restaurants outlet (replacing a local operator, Daniel's Deli), Saladworks Inc. (into a vacant spot) and other chains. Next, the Gap. Sales at the bellwether tenant were dragged down by its 1980s-era exterior -- red neon sign and blue Formica facade. It was often confused with a discount outlet -- a "dump store," Mr. Daniel says. To persuade it to spiff up, he showed Gap executives the company's own sales receipts from King of Prussia to show many Pottstown residents were shopping there. To find extra room, he refused to renew the lease of its neighbor, Everything 99 Cent, doubled the Gap's size and installed a new look: blond wood, sleek glass and a new navy-blue sign. Mr. Daniel used Gap's subsequent success to sell Coventry to Aeropostale Inc., Pacific Sunwear of California Inc. and Limited Brands Inc. While physical renovations can help faltering malls, getting undesirable tenants out is more important. Sometimes Mr. Daniel has to get tough. To force out Musselman's Jewelers, which generated only $467,000 in sales in 2001, he rented a spot across the hall to a Zale Corp. store, which generated about $900,000 in 2002. The Musselman's closed about two years ago. "They didn't want to go, so I helped them," Mr. Daniel says. Randy McCullough, chief executive of closely held Samuels Jewelers Inc., of Austin, Texas, which operated the Coventry store in 2000 and 2001, says he isn't sure whether competition hurt or helped. Next, Mr. Daniel plans to shave 100 feet off from the old Bradlees space to make room for a new "pad" -- a parcel in the middle of the parking lot suitable for a restaurant -- without losing parking spaces. As for that Arby's, Mr. Daniel says he has plans for its space when its lease is up, in 2008: Knock out a wall, build a new entrance from the parking lot and lease the space to a sit-down restaurant that would pay higher rent. "I've got to uproot just one pine tree," he muses. Bob Cross, vice president for business development for Arby's Inc., a unit of Triarc Cos., New York, says the Coventry outlet's sales are above average, despite having been hurt by another Arby's that opened less than a mile away. Mr. Cross says the Coventry store's franchisee has no intention of leaving the mall, but might agree to move to a different location, for instance, the food court. And while the mall doesn't look much different from a few years ago, shoppers are spending more. Indeed, Coventry's vital signs are now good. Vacancies are 6%, while sales per square foot are $330, above the national average, from $240 before the do-over. Vickey Sihler, sitting on a bench with her five-year-old daughter, Abigail, says she started coming for the improved Gap and the Children's Place store, which opened two years ago. Still, she has a suggestion: "This place really needs to be fixed up." http://www.realestatejournal.com/propertyreport/retail/20040126-starkman.html?refresh=on |